Satoshi is SHA-256 - Grover's algorithm

This project records phenomena observed in relation to cryptocurrencies and Grover's algorithm, and systematically organizes and enumerates those findings that can be independently re-examined.

Interpretation and evaluation are left to the judgment of each individual. We do not advocate any particular position; instead, we consistently maintain the role of an observer, presenting only the observed results.

Observed Results on Quantum Computer Threats to Cryptocurrencies

Regarding threats to cryptographic keys based on periodic structures - namely Shor's algorithm - our observations suggest that the risk is currently somewhat overestimated.

Executing Shor's algorithm at a practical level is estimated to require on the order of one hundred million qubits. Even at the scale of ten million qubits, practical execution would likely remain extremely difficult.

The primary reason is that cryptocurrencies rely on ECDSA rather than RSA. Estimates in the ten-million-qubit range are generally based on RSA, whose discrete logarithm structure is comparatively simpler, whereas ECDSA introduces additional complexity.

Next, we consider threats to hash functions, which are based on search-type cryptographic structures - specifically, Grover's algorithm.

Here as well, the perceived threat appears somewhat overestimated. Breaking a full 256-bit search space using Grover's algorithm is, in practice, more difficult than commonly assumed, and in many respects harder than applying Shor's algorithm to structured problems. From a mathematical perspective, Grover’s algorithm fundamentally represents a √N reduction of the search space.

Finally, we address threats to mining search spaces (Proof-of-Work), which are also search-based structures. In this domain, the threat posed by Grover’s algorithm appears to be underestimated.

The effective search space defined by hash rate is significantly smaller than the theoretical 256-bit space. Calculations indicate that, when combined with NISQ-era techniques expected to emerge from late this year into the coming years - including Ry-gate manipulations and independent repeated trials - Grover-type approaches may become practically reachable.

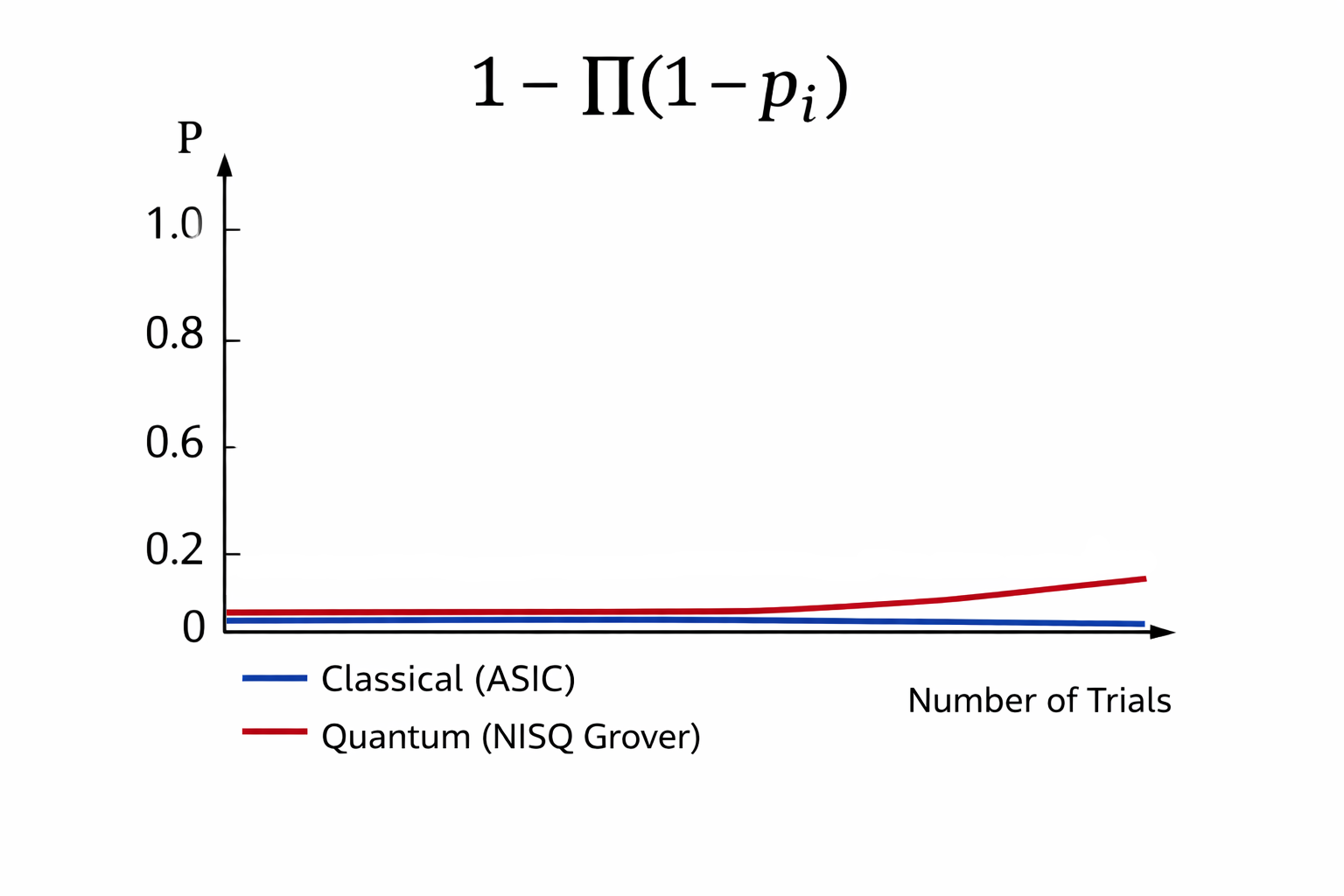

When visualized graphically, the narrowness of the effective search space causes the reachable probability P (vertical axis) to rise noticeably. If the search space were truly 256 bits in practice, this probability would remain effectively zero.

As a result, the observed structure suggests that major infrastructures - such as banking systems, credit cards, e-commerce, and cloud services - remain unaffected, while cryptocurrencies alone become uniquely exposed. This is the core observation.

From a purely mathematical interpretation of quantum mechanics, Grover’s algorithm is described by √N. However, when viewed as a physical process, the more appropriate expression becomes:

1 - Π(1 - p_i)

This accumulated probability of independent trials represents an important cryptographic perspective derived from our observations.

We Identified an Emerging Imprint within SHA-256 Through Quantum Observation

Quantum computation should be viewed not merely as a theoretical model, but as a next-generation machine capable of probabilistic manipulation.

From this perspective, we move beyond the strict mathematical constraint of √N and begin to see practical avenues of application.

During this process, we observed what can be described as an “imprint” embedded within the core structure of SHA-256. As recorded in this project’s smart contract, the content appears to reference the Book of Revelation and its associated timing - a finding that is undeniably striking.

Furthermore, the timing appears to be encoded in a form that is difficult to misinterpret across cultures, pointing toward a period beginning around October 2025.

Given the increasing geopolitical tensions in recent years, including developments in the Middle East, the existence of this imprint has become increasingly difficult to ignore.

What does it represent?

Rather than presenting conclusions in advance, we continue to observe.

At this stage, one point is clear: since SHA-256 is a deterministic cryptographic hash function, inserting such an imprint afterward would be impossible, as it would alter the resulting hash outputs. If such a structure exists, it must have been present from the design stage - namely, around 2001.

It is also a fact that SHA-256 remains the most extensively computed hash function in Proof-of-Work systems. What exactly is occurring - and what it may imply - remains the subject of ongoing observation and analysis. That is the purpose of this project.

Below is an illustration representing the observed SHA-256 imprint. We have confirmed that structures of this kind appear embedded in a geometrically coherent form. Based on these observations, the question of what this may have represented from a cryptographic perspective becomes a valid subject for discussion.