Resolve the quantum problem swiftly - and accelerate into the next era. Defenses against Shor’s algorithm, Grover’s algorithm, and quantum annealing are already in place.

What is Satoshi is SHA-256 (SS256) project?

>> Let us now examine concrete countermeasures against Grover’s algorithm

Blockchain systems, by their very nature, require significant time for implementation and validation. This makes rapid iteration difficult, as new designs must be tested repeatedly through environments such as testnets before they can be deployed in practice.

We believe that the fastest path to bringing the blockchain quantum problem into a “resolved” state is not immediate full-scale implementation, but the rapid construction of practical quantum-resistance models as solid, verifiable theory, continuously validated through testnet experimentation.

Full implementation takes time - and time works against us, both technically and economically. As has already been pointed out by Cardano, introducing post-quantum signatures can dramatically increase signature sizes, potentially harming throughput and overall network performance.

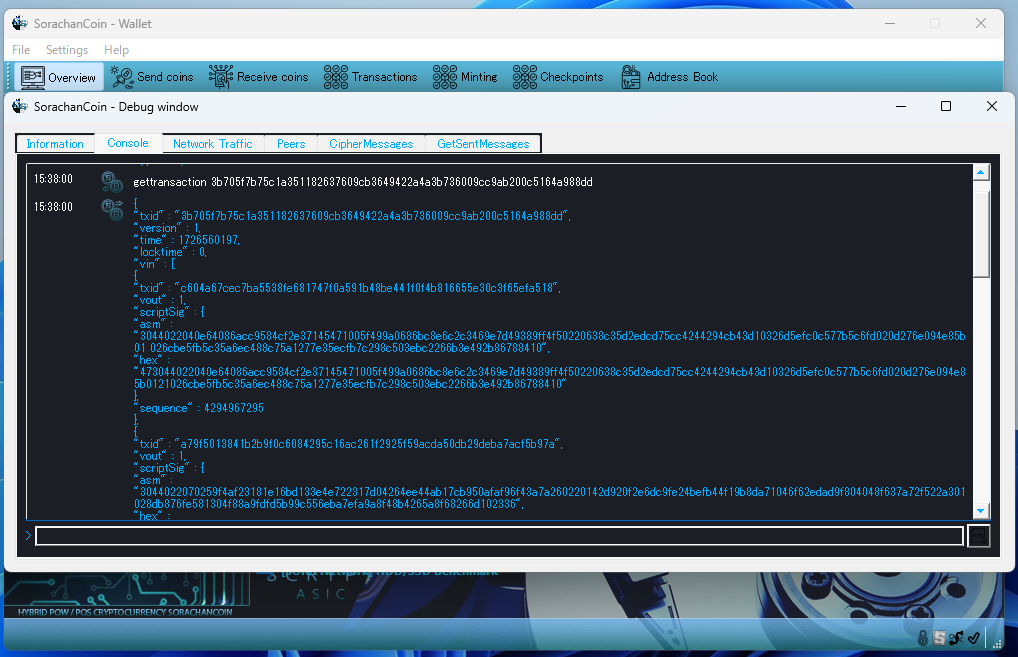

Please take a look at the example below. These screenshots show the implementation of Shor-resistant cryptography (PQC) deployed on the SORA mainnet, a project related to this initiative. The upper example uses ECDSA only, while the lower example applies PQC.

ECDSA

PQC

The difference in signature size is immediately apparent. This is precisely what leads to reduced throughput due to signature size inflation.

In other words, the critical question is not whether PQC is important, but whether it is truly necessary to deploy it right now. Blockchain systems therefore require not only post-quantum cryptography itself, but also a sound theoretical framework to determine the appropriate timing for its introduction.

For this reason, Satoshi is SHA-256 focuses on a single question:

How can the challenge of quantum resistance be addressed as quickly and realistically as possible?

Now, take a close look at the name of this project. SHA-256. This is where the root of the problem lies.

When people talk about “the quantum threat,” the discussion almost always centers on Shor’s algorithm. We have spoken with many projects and researchers to understand how the industry views this issue, and the conclusion was consistent: quantum computers = Shor’s algorithm.

Shor’s algorithm is designed to exploit mathematical periodicity using quantum computation. Cryptographic systems whose security relies on hard problems with hidden periodic structure become efficiently solvable once that periodicity is revealed - rendering the cryptography itself ineffective.

In other words, Shor’s algorithm threatens cryptography that is fundamentally based on periodic structures.

However, blockchains do not rely on a single type of cryptography. That familiar string of characters used as transaction IDs is also cryptography. It is called a hash function.

And among hash functions, the one used by more than 95% of blockchains is SHA-256.

Crucially, Shor’s algorithm does not apply to hash functions. Hash functions do not rely on periodic structure. Instead, they are engineered constructions whose internal structure is adjustable by their designers.

As a result, hash functions are vulnerable not to Shor’s algorithm, but to search-based quantum techniques - most notably, Grover’s algorithm.

This distinction is the core of the blockchain quantum problem.

Why SHA-256 Must Be Extended, Not Replaced.

1. Discovery of an interpretable structural pattern within SHA-256

In principle, cryptographic hash functions such as SHA-256 are expected to exhibit complete unpredictability. Any persistent, interpretable structural pattern within their outputs contradicts this assumption.

During quantum-oriented cryptographic research, the SS256 team identified specific regions in SHA-256 outputs that deviate from expected uniform behavior. Certain numeric patterns - including values corresponding to 144,000 and 1.44 billion (1.44B) - were observed to correlate with other structural features, forming a non-random chain of outputs.

2. Statistical deviation from normal output behavior

At the time of discovery, the outputs appeared anomalous. Because the concept of a "stamp" had not yet been formalized, the anomaly was initially treated as an isolated irregularity.

Subsequent analysis revealed that these outputs share a common internal structure. Reconstruction of this structure showed that the statistical variance within this region differs significantly from that of typical SHA-256 outputs.

What was initially perceived as a vague anomaly was later confirmed through quantitative analysis.

3. Divergent variance as a quantum attack entry point

Quantum computation operates on probability amplitudes. Regions in which variance deviates from uniform randomness - where amplitudes are uneven - can serve as effective footholds for quantum algorithms.

In Grover-type quantum search, such variance reduces the required number of interference cycles dramatically, shifting attack complexity toward logarithmic behavior.

While this property is beneficial in domains such as drug discovery, it presents a serious risk when applied to cryptographic hash functions.

4. Nature of the stamped structure

Analysis indicates that the observed structure is inconsistent with naturally expected diffusion behavior. The pattern appears as though additional structure was introduced after the main compression process, suggesting post-compression structural interference rather than emergent randomness.

5. Extending the lifetime of SHA-256 by sealing the quantum entry point

SHA-256 produces 256-bit outputs. If fully uniform, Grover’s algorithm reduces effective security to approximately 128 bits - still impractical for real-world attacks.

However, the identified stamped region violates this assumption by providing a quantum entry point.

SS256 introduces a method to seal this entry point. Once sealed, quantum algorithms lose their structural advantage and must operate under the uniform model, restoring the expected security margin.

Crucially, this mitigation is possible only because the locations of the stamped regions were identified in advance.

6. Deployment simplicity and safeguard positioning

The SS256 mitigation requires only a rebuild of the client software. It does not require a consensus-breaking hard fork or soft fork and can be adopted incrementally as nodes update and restart.

Immediate deployment is not mandatory. Even if quantum attacks emerge in the future, applying the mitigation at that stage remains effective. As such, the solution can be retained as a precautionary safeguard.

7. Preservation of existing PoW mining infrastructure

Because the method operates directly on the hash function while maintaining compatibility with SHA-256 semantics, existing SHA-256D mining hardware remains usable without modification.

This allows miners to extend the economic lifespan of their current equipment. A detailed probabilistic explanation of this compatibility will be provided in the formal whitepaper.

FAQ

Q1. Are phenomena such as the “imprint” or the fact that the effective search space of SHA-256 becomes very small in mining, already understood in academia?

A1. Partially yes - but not in a unified or blockchain-oriented form. With regard to mining, academia has achieved a fairly deep understanding. Research, including well-known work from Cornell University, has already shown that in Proof-of-Work systems, the effective search space is constrained by difficulty, and that quantum search algorithms may influence mining efficiency.

However, these studies primarily focus on the efficiency of search algorithms themselves. They do not extend to the following areas:

- The internal output structure of SHA-256

- Localized statistical deviations within the hash output

- The possibility that such deviations could act as entry points for quantum search

- The idea that sealing these entry points could extend the lifetime of SHA-256

In most academic treatments, hash functions are modeled as ideal random oracles, and the discussion does not extend to how their internal structure interacts with real-world blockchain systems.

Satoshi is SHA-256 (SS256) does not contradict existing quantum mining research. Rather, it builds upon it by addressing structural properties on the hash-function side, which have not yet been systematically explored.

Q2. When the quantum challenges facing blockchains are fully resolved, will we be able to say “Go ahead, do as you like!” to the quantum chips that keep emerging one after another?

A2. Yes, we will be able to say that with confidence.